(Uncle Bill, circ maybe 1960)

Uncle Bill (1.6.2) was born February 20, 1874, at Searsboro, Iowa. He was the second child born to John Wesley and Sarah Vincent Hughes and was blessed with remarkable endurance, a powerful physique, and a mental toughness that carried him through a career that involved back packing over the Chilkoot Pass (See Stampede, page 38) ranching, mining, oil fields, road and bridge building, freighting and too many narrow escapes to mention.

He had terrific ability to rebound from what would be disaster for anybody else. His skill handling a freighting unit consisting of many teams of horses was legendary. When the Montana Power Co. built the dam and powerhouse in the Madison Canyon, Uncle Bill contracted to haul the turbines from the railhead to the canyon site. He accomplished this with eleven teams, (22 horses) pulling a huge stone-boat (sled-like skid vehicle) on which was loaded one turbine.

Bill survived three wives. He was married to Bessie Clark in 1903, who tragically died in 1923, while they were living in Greybull, Wyoming. Bessie was the mother of their four children: John, William, Ina and Sarah. In 1933 Bill married Adi Real, who died in 1944, then he married Carrie Templin, who died in 1947. Bill lived to the age of 98, dying April 30, 1972. He is buried in the McAllister, Montana cemetery.

Bill was not reluctant to talk about his many adventures, prominent among them was a trip to Alaska to the Klondike Gold Fields with his father. He related vivid accounts of having back packed over the Chilkoot pass and of whipsawing lumber for boat building on the shores of Lake Bennett and Lake Lindeman. These activities were at their peak during the stampede. Although Bill reckoned he was "about 19" when he went to Alaska with his father, his stampede experiences are indicative of a time frame more appropriate for when he was a few years older, probably 1897 or 1898.

One of the details indicating that they were present at the height of the stampede is that they were too short of money to procure the required supplies required; so Bill paid their way by back packing supplies over Chilkoot Pass on "commission" for other stampeders. The Canadian RCMP had established a requirement, in 1897, that each stampeder had to have 1700 lb. of supplies. A cable tramway to the top of the pass was completed in late 1898 so Bill's packing for hire over the Pass was probably before the tram was completed.

In any event, they did not stay long in Alaska, all of the good claims in the goldfield had been staked and the only livelihood was working for somebody else. Their Alaskan adventure ended with John W. getting sick. They only had money to get both of them to Seattle by boat and John W. home to Iowa on the train. Bill worked his way home, chiefly with a freighting job in Idaho.

In 1899 Bill went west to Montana with his older brother Edwin, the first Hugheses to make the move, soon followed by John Wesley, Sarah, and the rest of the family.

(More about Uncle Bill 38. Read about the Alaskan gold rush and Bill’s trip to the frozen north.)

Click on Martha Hughes Rich "Memories of a Plain Little Girl for a handwritten article about the family by one of Bill's sisters.

Composed and submitted by: Bob Hughes, April, 1999

**************************************

More About WILLIAM MILTON HUGHES

The following excerpts from articles written about the Alaskan stampede provide an insight to the trip that J. W. and Bill made to Alaska.

STAMPEDE

From: Land of the Midnight Sun,

A History of the Yukon

By: Ken S. Coates & William R. Morrison

George Carmack, Skookum Jim, and Dawson Charlie struck gold in 1896 at Rabbit Creek, which was then renamed Bonanza. By 1898 the largest gold rush in history was on. 100,000 gold seekers from around the world set out for the Klondike; 30,000 reached their goal of Dawson City.

Getting there was half the battle. Stampeders trekked over the treacherous Chilkoot Pass with a year of supplies -- 800 kg (1,760 lb.) -- to ensure survival. Arriving at Lake Bennett, they cut trees and built boats, and waited the winter. Then, as soon as the ice broke, they set sail for Dawson down the Yukon, a fast-flowing river notorious for its mean rapids.

Dawson, a city that didn't exist in 1896, had a population of 30,000 by the late 1890s, making it the biggest city north of San Francisco.

Gold dust was more plentiful than snow, whiskey flowed faster than the Yukon River, and with a bar on every corner and legendary ladies like Klondike Kate in the dance halls, Dawson was the good time capital of North America. If you struck gold, you were rich beyond your wildest dreams. Today, placer mining is still going strong.

PACKING THE CHILKOOT PASS

From the book: THE KLONDIKE FEVER, by Pierre Berton.

"An unbroken line of men, stretching into the cold skies, provides the stampede with its most memorable spectacle on the slopes of the Chilkoot Pass."

'Gold was discovered at Rabbit Creek, later changed to Bonanza Creek, in the Klondike area of the Canadian Yukon in the summer of 1896. This news, filtering out from Forty Mile, where the first claims were filed by George Carmak and two Indian friends, Jim and Charlie, set off one of the more spectacular gold rushes of the North American continent. The news spread like wildfire; and all over America, indeed all over the world, adventurous men and women headed for Skagway, Alaska, in an eager rush to the gold fields.'

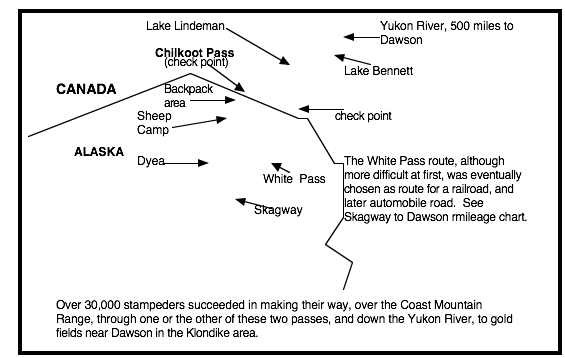

It was a five day boat trip from Seattle to Skagway. At Skagway a choice had to be made to go over the White Pass route (called the Dead Horse Trail because of the number of horses killed trying to pack their relentless masters and their goods) or to back pack over the Chilkoot Pass route. Both routes would eventually lead to the Yukon River for a float trip down to the Klondike. Two drainage lakes, Lake Lindeman and Lake Bennett formed the headwaters of the Yukon River. Stampeders making it as far as the Lakes had to build, or have built, or somehow contrive possession of some kind of craft to float the last 500 miles to the gold fields near Dawson. Those who chose the White Pass route would leave their ship from Seattle at Skagway. Chilkoot Pass travelers would start from Dyea at the end of the inlet. Both places were boom towns that sprang into being at the news of a gold strike. They had no docks or piers at first and all goods had to be unloaded into smaller boats to get ashore. Skagway survived to become a permanent Alaskan feature, but Dyea only survived for the three years of the gold rush.

In 1897-'98, the North West Mounted Police set up a border crossing into Canada at the summit of the Chilkoot. They ordered every stampeder to carry a year's worth of supplies. After all, there was no turning back once they were into the Klondike, and commerce was limited, to say the least. As a result, many stampeders struggling up the mountain were bent double under the weight of their packs.

In 1897-'98, the North West Mounted Police set up a border crossing into Canada at the summit of the Chilkoot. They ordered every stampeder to carry a year's worth of supplies. After all, there was no turning back once they were into the Klondike, and commerce was limited, to say the least. As a result, many stampeders struggling up the mountain were bent double under the weight of their packs.

The trail from Dyea to Sheep Camp (see map) was comparatively easy as it did not climb much and horses could go that far. In the next four miles, from Sheep Camp to the check point on top, the trail would rise 3500feet with only two places wide enough for a rest stop. It took hours to get back in line if you stopped to rest. In places the slope was nearly vertical. Steps had been cut into the glacier ice but even so it took most stampeders six hours to go up with a 50 lb. pack. Many trips had to be made to get the required 1760 pounds of supplies to the top. Coming back down was a snap. The packer just sat down and slid to the bottom on his rump.

______________________________________________

It was commonplace, for those without the strength and endurance to backpack 50 to 100 lb. loads, to hire packers to help take their stuff up. In addition to a group of professional packers available to do this work, members of the various Tlinglit Indian tribes, native to the area, were excellent packers. The price started at $1.00 per lb., but was subject to change if somebody came along with a better offer. The professionals handled 100 lb. packs as a matter of course, even more if the incentive was great enough. An Indian packer is said to have reached the top with a 350 lb. barrel on his back. A Swede crawled up on his hands and knees with three huge 6 x 4 timbers strapped on. Various bets and contests created not only new back packing records, but new tall tales for the folks back home.

Today, many adventurous hikers re-trace the steps of the Klondike stampeders, but their burden of supplies has been lightened, to the extent that adequate supplies now fit in one backpack.

An aerial tramway was built and put into operation in December of 1898, effectively putting the back packers out of business. The tram had a steam engine at both ends and 14 miles of steel cable. Some of the heavy machinery and cable had to be packed and dragged to the top; that was the hardest part of the construction.

The two lakes, Lindeman and Bennett were a beehive of activity with people of all description hastily fashioning some kind of a raft, scow, boat, barge, canoe, anything, to float themselves and their supplies down the Yukon River. They desperately wanted that to be done before freeze-up time. Several thousand stampeders arrived too late and had to spend the winter of 1896 in crude camp villages along the lake shores

A railroad was blasted through the mountains from Skagway to Whitehorse, along the White Pass trail, and completed late in December, 1899. This enabled big companies to bring in dredges and heavy equipment. New strikes had been made up around Cape Nome so hordes of stampeders left the Klondike for the new gold fields.

The famous Klondike stampede was over. It lasted almost exactly three years from when George Carmak and his Indian friends, Jim and Charlie, made their discovery in the summer of 1896.

An automobile road, State Highway 2, now goes the route, as does the railroad, of the original "Dead Horse Trail"

**************************************